What Sony's Accessibility means to us

What Sony's Accessibility means to us

Designing products and services for a "world with no limitations"

Sony Group incorporates accessibility into products and services for a future where everyone shares the moment. Our style of "inclusive design*" encourages a diversity of individuals to work together. In this article, four individuals deeply involved in Sony's creations explore what this accessibility means to them.

- *Inclusive design stresses inclusivity by embracing a diversity of product users, including those with disabilities, as shared understanding is incorporated into the design process.

Profile

Moderator: Amari Eriko

Moderator: Amari ErikoGeneral Manager, Quality Management Department, Accessibility & Human-Centered Design Group, Sony Group Corporation

Amari leads accessibility and human-centered design (HCD) initiatives within the Sony Group.

Ito Yoichi

Ito YoichiTV Peripherals Design Section, Product Development Department,

TV Business Group, Sony Corporation

Ito is the Design Product manager in charge of the Wearable Neck Speaker and Wireless Handy TV Speaker, new-category TV peripheral devices.

Inoue Kensuke

Inoue KensukeGeneral Manager, Claims Service Department 2, Claims Service Division, Sony Assurance Inc.

After joining the company, Inoue initially made system adjustments to improve service quality in the auto insurance division, but in April 2021, began supervising accident resolution service centers assisting customers in the Chubu Area.

Kato Ayumi

Kato AyumiTokyo Laboratory 08, R&D Center, Sony Group Corporation

Kato's area of expertise is research and development of interaction technology supporting modality fusion; blending all human sensory avenues from 2019, she has been engaged in research and development of accessibility utilization in user interface involving haptics.

Sonohata Hitomi

Sonohata HitomiInformation Solution Section, Diverse Business Department, Sony/Taiyo Corporation

In 2015, after producing microphones and audio/visual accessories, Sonohata shifted her focus to web-related work, creating and updating portal sites in the Information Solution Section for Sony Group companies.

Individual thoughts on a "world with no limitations"

— Sony's Accessibility message

Amari:Accessibility means "able to access." For instance, all of us, including the hearing impaired, can access language through subtitles or captions which enable us to enjoy movies. The power of technology allows each of us to find our own ways to enjoy rich experiences firsthand. The "world with no limitations" message suggests our desire to forge such a future together with users and creators.

Enabling diverse styles of enjoying TV Sony's technology creates new sound experiences

Ito:I develop TV peripheral devices like the Wireless Handy TV Speaker and the Wearable Neck Speaker. These days, a wide variety of content such as dramas, news, movies, live performances, and games can be enjoyed on TV in diverse ways to fit each person, place, environment, and lifestyle. For example, if you have these wireless speakers beside you, you no longer need to just sit in front of the TV, the speakers offer you new ways to hear and enjoy TV wherever you are.

Wireless Handy TV Speaker

Wireless Handy TV SpeakerSRS-LSR200

The Wireless Handy TV Speaker incorporates two technologies: one that enhances sounds and dialogue to hear clearly even when away from the TV and one that enhances hard-to-hear consonants. Normally speakers come as left-right pairs, but what we want to hear from the TV is clear words and audible dialogue, so we inserted a third dedicated speaker in the center to catch voice dialogue which is sometimes hard to hear under ambient noises. We also incorporate Voice Zoom technology, for crisper and clearer dialogue, further meeting individual needs when users generally have difficulty of hearing.

Amari:With the Handy TV Speaker, you do not need to increase the TV volume, endearing it to parents hoping not to disturb children studying for exams. It is extremely convenient for someone like me living in "an environment with limitations."

Ito:Right—we are focusing on not only these audio features but also usability enhancement by designing with visually impaired colleagues from the Prototype stage. Our goal is to create products that are easy to use for everyone.

Haptics technology—for all to enjoy

Ito:The Wearable Neck Speaker is another wireless product which you place on your shoulders. It has a vibration function that responds to sound naturally, creating a completely new and more realistic viewing experience. I recently had the chance to wear the neck speaker and the R&D group's "Haptic Vest" (a vest-like garment using technology that recreates realistic scenes through controls linking multiple vibration devices). The result was a fascinating experience with simultaneous tactile and audio sensations perceived through vibration and sound.

Wearable Neck Speaker

Wearable Neck SpeakerSRS-WS1

Sound

Sound Vibration

VibrationAmari:Kato-san, you have also been involved in the development of the "Haptic Vest" which incorporates our haptics technology, haven't you? How does that technology enhance product accessibility?

Kato:Braille blocks are the classic example of how information transmission becomes accessible through touch. The tip of white canes used by the visually impaired communicates differences in texture on the ground, helping them to figure out their current location. The field of haptics technology, which artificially simulates tactile information, is gaining ground, partly thanks to VR. For instance, until recently, cell phones have only offered a rudimentary vibration function. Now, however, advancements in both devices and technology have enabled the creation of more versatile and varied expressions. The ability to communicate a sense of realism or a texture and other new modes of expression have made the fields of games and smartphones even more exciting.

Product development using haptics technology has enhanced the sense of touch associated with machines. I am interested not only in that physical aspect, but also in how human beings experience the sense of touch, which is what I am currently researching. Each of us experiences touch differently; age is a factor, of course, but there are also areas of the hand which have greater-and lesser-sensitivity. How can we express tactile information that provides everyone with an understandable and enjoyable experience? I integrate these human factors into my approach as I carry out R&D work.

Inclusive design realizes new experiences by involving individuals with disabilities

Amari:As a special subsidiary of SONY Group Corporation, Sony/Taiyo Corporation hires many people with disabilities. The company pursues monozukuri manufacturing as a team regardless of ability or disability.

Kato:I conduct R&D field work together with Sony/Taiyo employees such as Sonohata-san who have a visual or hearing impairment. That involves having them test haptic device prototypes, but we also share meals and other daily routines to deepen our understanding of their daily challenges. This approach has enabled all of us, developers and employees with disabilities alike, to discover issues together.

At the R&D Center, we also depend on the cooperation of our employees with disabilities to help test our prototype; we incorporate their feedback and—through trial and error—create a solution using haptics technology addressing issues identified through fieldwork.

A work in progress

A work in progressSonohata:One new project on which I collaborated with Kato-san involved enabling viewers to feel the mood of the scenes and voices expressed through sound on smartphones and TV. People like me, who read TV captions because they are hearing impaired, don't know how it feels to hear people laugh, and this project helped me experience that, which was amazing.

To tell the truth, when I first began working on development with Kato-san, I was unable to speak frankly about my disability and its challenges with the developers. I have had my impairment since childhood and it is second nature to me, so there are inconveniences I don't even realize, and many issues needing solutions. The developers visualized problems they imagined we face, and repeatedly brought prototypes for us to test. As a result, a relationship of trust gradually emerged, and I began to communicate my true thoughts. Unless I spoke up, I would never be able to enjoy user-friendly items. Now I feel that my input, added to the developers' repeated cycles of creating prototypes, ultimately yielded excellent products.

Kato:When I first asked those with disabilities about their challenges, they were often unable to identify them, as those challenges are embedded in daily life. I suspect the response would be vague even if I pinpointed specific inconveniences. For that reason, I think involving all members in a repetitive development process was effective.

Amari:That precisely illustrates the inclusive design process on which we are working. It means collaborating on challenges with the diversity of users who face limitations. We can gain broad awareness through the development process, resulting in useful and convenient products and services which help many people.

Sony Assurance's Sign Language/Conversation-in-Writing Service* Comfort for everyone during emergencies

- *This service is only available in Japanese language.

Amari:How does Sony Assurance help individuals with disabilities, for whom making a telephone call is difficult?

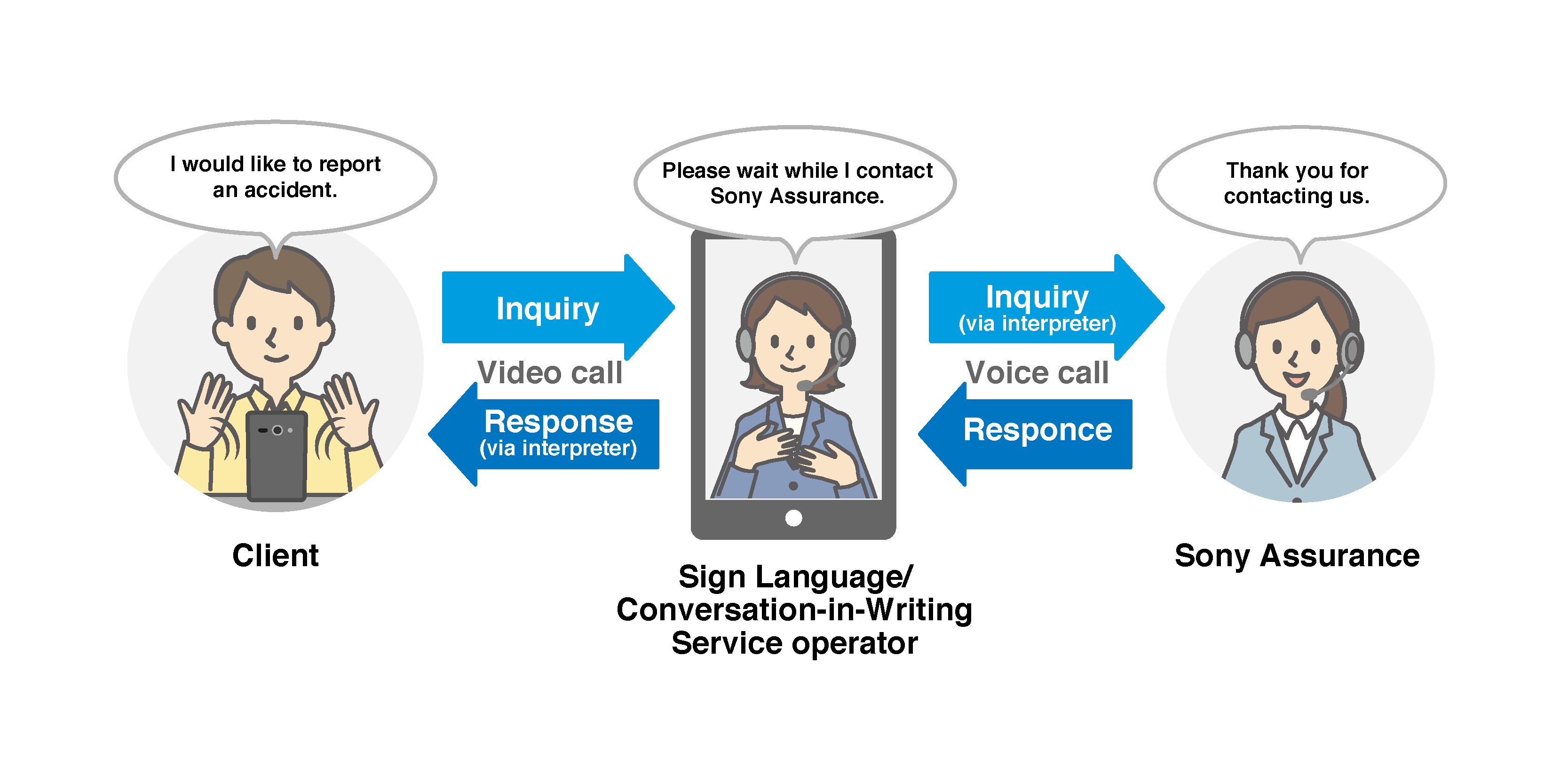

Inoue:Sony Assurance offers the Sign Language/Conversation-in-Writing Service which, with the aid of operators, enable us to help the client even when telephoning presents a challenge. Before these services were available, we often communicated by fax, e-mail, bulletin boards on our website, or a third party acting in our stead. However, those methods did not allow for real-time interaction, and when I recall them now, I feel that time lags and relying on a third party must have been frustrating for our clients.

The first client who used this service left a lasting impression on me. After a car accident, the client's father telephoned us, but once we told him about our Sign Language/Conversation-in-Writing Service, our client was able to contact us directly. Negotiating car accident resolutions requires accurate assessment of the situation and the other party's intentions, which is challenging enough by telephone; utilizing a third party and relying on written language alone is often insufficient. I realized through personal experience that communicating directly benefits both the client and the company.

Amari:Sonohata-san, does the Sign Language/Conversation-in-Writing Service offer you a sense of security?

Sonohata:If I cannot use the phone to communicate when a car accident occurs, I often cannot contact the other party either, and going through a third party is time-consuming. I found it helpful to have the two additional options offered by the Sign Language/Conversation-in-Writing Service.

Inoue:I'm delighted to hear that. We are also implementing universal design to make insurance claim documents visually clearer. Right now, we are working with colors and font sizes to improve the process. Customer services are all too often linked to cost-effectiveness and volume. However, I am redoubling my efforts to ensure that no customer feels left out and that each finds our services convenient.

Toward a future which leaves no one behind

Amari:In terms of a "world with no limitations," what sort of future do you envision personally or as part of the Sony Group?

Sonohata:If I hadn't joined Sony/Taiyo and begun communicating with developers, I surely would never have considered accessibility. Since I have an impairment, I always assumed it was up to others to deal with my accessibility. But now I realize that if I plan and communicate through teamwork, I can help create user-friendly things. Sony produces a variety of items, and I have often felt the joy of experiencing something newly accessible. If we consider accessibility from diverse viewpoints, we can produce innumerable joyful experiences. That is why I hope to continue collaborating with others on development and help create even better things through monozukuri.

Ito:In my work as product developer, I'm not just designing products but creating new "experiences." So I hope to continue boosting the company's vision of creating experiential value.

I dream of a world where each person can enjoy and experience things which were previously inaccessible through direct sight or sound. The Wearable Neck Speaker frees you from "the limitations of place." Even if you are unable to attend a Live concert, the speaker lets you feel you are there though you are physically at home. Being freed from spatial limitations is so exciting and inspiring. My wish is to be a person—and part of a company—that creates such experiences with no limitations. In addition, the Handy TV Speaker sparked gratitude in many people. It's been nicknamed as the "parent care appliance," and many parents have voiced their appreciation with uplifting expressions: "Exciting," "Inspiring," and "Thankful." My goal is to help more individuals feel these three words that come from the heart.

Kato:The coronavirus pandemic has reduced our opportunities to experience touch. I've read articles about the emotional pain suffered by those overseas who can no longer hug each other. As a haptics engineer, I'm searching for ways to use the power of technology to help during this time in which touch is restricted. Contactless elevator buttons are now on the rise, but I worry that this contact-free trend may leave some individuals with disabilities behind. In times of upheaval such as now, I feel an even stronger wish to create new ideas for the future together with diverse users to ensure that nobody is left behind.

Amari:The key point is that every individual faces some kind of limitation. Inclusive design starts with identifying limitations found in daily life. We utilize that information to create products and services for the future. We pursue inclusive design with a diversity of individuals to overcome limitations surrounding us. All of us at Sony hope to create a future where everyone shares the moment by incorporating accessibility into our products and services.